December 13th, 2008

The Royal Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), known in Bengali as bagha or shardul, is the largest member of the cat family on the face of the earth. A male specimen averages 9 feet 5 inches from head to tail and weighs approximately 480-600 pounds. The female measures around 8 feet and weighs in the region of 300 pounds. Its canine teeth can be up to 5 inches long and its claws are razor sharp. It is said that a Royal Bengal tiger can kill an elephant or carry a fully grown cow over a ten foot fence. In its natural habitat, it stands indisputably at the top of the ecosystem – and it is the national animal of both Bangladesh and India.

Imagine then that you are just ten years old, alone in the forest, your eyes eagerly scanning the foliage above your head for the rust-coloured drupes of jujubes that you crave. You climb up one of the jujube trees and eat some of the sweet, crunchy fruit. Then you clamber down the tree, keen to embark on more adventures. Suddenly, something draws your attention to the long grass in front of you. As your eyes adjust to the shadows, you see them coalesce into black stripes on orange fur, a massive head with two gleaming eyes is turned towards you – and you realise that you have come face-to-face with an enormous Bengal tiger in the wild. The forest around you is utterly silent. There is no adult within a two-mile radius, no means of help, no weapon to hand, no building to hide inside. It is just you and the tiger; a young boy at eye-level with one of nature’s most ferocious creatures. Your life can be measured in seconds.

This is the exact scenario that unfolded sometime between 1941 and 1942, when spiritual luminary Sri Chinmoy (known as Madal) was ten years old. It took place in the low mountains to the east of Chittagong, an area which in those days was still densely forested and where tigers and other wild animals ranged freely.

Over the years, Sri Chinmoy narrated this heart-stopping story a number of times. Sometimes, in his retelling, he substituted the word ‘lion’ for ‘tiger’ and this has created inevitably some confusion, especially since the Asian lion was not known to still inhabit that area. I once had the opportunity to ask him personally which animal it was that he encountered on that fateful day and he answered, emphatically, “Tiger! Tiger!” I imagine that, in the drama of the moment, he did not take account of the precise physical characteristics of the big cat that was poised not ten feet from where he stood. From the descriptions of those few who have survived to tell such a tale, it has been observed that in life-or-death circumstances, one isolated detail often becomes the focal point of concentration and the thing that is remembered long afterwards. It can be something as inconsequential as the way the leaves rustled, the shape of a cloud or a certain fragrance. In Madal’s case, it was the eyes of the tiger. Beyond these, it appears, he saw little else. In later life, he continued to interchange ‘lion’ and ‘tiger’; he never referred to its size, whether it was standing or crouching, upwind or downwind of him, if it was male or female. But he always described the look in its eyes.

For up to five minutes, Madal and the tiger gazed at each other, neither one making a move. The tiger made no motion to leap at him, nor did Madal run away or scream. Something quite extraordinary had intervened to transform his emotions from those of fear to those of calmness: he saw his mother’s eyes reflected in the eyes of the tiger and she was inundating him with love and affection. Here is the entire episode in Sri Chinmoy’s own words:

“When I was ten years old, I went to visit my maternal uncle who lived in the country. There was a chain of mountains nearby, about two and a half miles away. I was extremely fond of roaming in these mountains.

One afternoon about two o’clock, all my friends were in school, so I decided to go for a walk alone on one of the mountains. I had been to this mountain many times accompanied by my friends and relatives. But we had only wandered through the fringes of the mountain, which were more accessible. This time, being alone, I got more joy from my adventure! I roamed further and further until I was in the thick of the dense forest which covered the mountain. Formerly, when I had gone with my friends and relatives, they had wandered only through the outskirts of the forest, as these were more accessible.

I was very fond of a certain kind of fruit called jujube. There were many jujube trees in the forest, so I climbed one of them and ate to my heart’s content. When I climbed down, there, facing me, only ten feet away, was a tiger!

We stood there, face-to-face, and the tiger, far from showing a ferocious look, was all mildness. Furthermore, reflected in the tiger’s eyes, I saw the face of my own mother although my mother was in our home village, Shakpura, six miles away.

This went on for several minutes. Seeing my mother in the eyes of the tiger, I felt no fear and raised no cry. I was calm and serene. The more I looked into the tiger’s eyes, the greater was the affectionate feeling I received from the tiger.

Very slowly, after about five minutes, I started to move away, turning my back to the tiger and walking slowly and cautiously. After covering a reasonable distance, perhaps a quarter of a mile, I turned back to see if the tiger was following me. There was no sign of the animal. Then I took to my heels and ran for dear life.

I covered a mile in a short time, crying and shouting for help: “Save me! Save me! I saw a tiger!” When I finally came to my aunt’s house, I was trembling and screaming. My aunt felt as though I had died and had come back to life by some miracle. Some of the villagers showed sympathy, some scolded, others mocked. My aunt was holding me as if I had really been killed by the tiger!

Although it had been decided that I would be staying at my uncle’s home for a few days, quite unexpectedly my mother arrived that day. In the afternoon she had been having a siesta, and had dreamed that I was attacked and killed by a tiger. She came with her servant to her brother’s home, practically insane with grief, assuming that her son had died.

I was practically bathed in the sea of tears shed by my mother and aunt in their joy at seeing me alive and safe.” 1

Clearly, the tiger’s decision not to attack cannot be ascribed to the fertile imagination of a young boy. Although a tiger attack may well be the most fearsome thing the human imagination could ever conjure up, imagination alone cannot quell the destructive power of a living animal.

And yet, it is difficult to explain how Madal’s intense inner experience could have such an immediate and decisive effect on the physical plane. Several explanations suggest themselves. One is that in his moment of utmost need, when there was no other recourse for help, Madal was able to invoke his mother’s calm and serene presence to such a degree that the tiger was subdued. A second explanation suggests itself when we learn that at the precise moment Madal was having this experience, his mother dreamt that he had been attacked and killed. Because of their close inner connection, it is highly likely that her soul became aware of the danger he was in and exerted itself to protect him by entering into the soul of the tiger. A third explanation is that the young boy was protected by God Himself who entered into the tiger and rendered it incapable of attack. It is possible that God manifested Himself through the eyes of the tiger as Madal’s mother so that Madal would not be afraid.

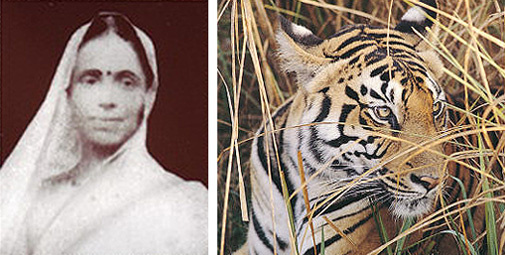

The eyes of Sri Chinmoy’s mother, Yogamaya, and the eyes of a Bengal tiger are juxtaposed below:

Photo credits: Sri Chinmoy Centre/Ullas Karanth, WCS-India

Again, a sceptic might say that tigers are shy and secretive animals which tend, by nature, to avoid human contact. Alternatively, the animal may have already feasted or perhaps it preferred some other kind of prey. Atanu Raha, chief conservator of forests in West Bengal, stated in 2003: “Human beings are not a natural diet for tigers. A tiger turns into a man-eater only under extraordinary situations, like when it grows too infirm or disabled to hunt or when there is a scarcity of its natural prey.” Nonetheless, the tiger is responsible for more human deaths than any other predator – and most of these killings are cases where the victim accidentally surprised a tiger.

While not claiming to be an expert on the habits of tigers, I believe that the encounter between Madal and the tiger may have been one of those extraordinary situations to which Atanu Raha refers, and in more ways than one. From the tiger’s point of view, it was clearly extraordinary to have been presented with such an easy and defenceless prey, one moreover which had intruded into its territory. From Madal’s point of view, it was extraordinary that his life was spared. Beyond the extraordinary lies the mystical and it is within the bounds of mystical experience that this incident falls.

“A real mystic,” explains Sri Chinmoy, “is he who wants to see the divine mystery in everything, in nature and in human beings. He wants to go to the essence, to the Source, faster than any human being dares to imagine.”

In this case, in the fraction of an instant, Madal was able to see the divine mystery inside the tiger, to penetrate its essence, as it were, with the result that the whole scene has a transcendent quality.

Sri Chinmoy carried this experience with the tiger with him throughout his life in a number of ways. He was once asked which was his favourite poem in English and he stated that it was “The Tyger” by William Blake, and he described this poem as “humanity’s invaluable treasure.” The immortal opening stanzas of the poem are:

“Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?”(From Songs of Experience, 1794)

Sri Chinmoy offered his own illumining interpretation of this poem in his talk on William Blake given at the United Nations in New York in 1976:

“Here we see that ignorance-energy, which threatens to devour the entire world, finally discovers its transformation-salvation in the realisation of the absolute One. This absolute One embodies both ignorance-energy and knowledge-energy and, at the same time, far transcends them both.” 2

Interestingly, both Blake and Sri Chinmoy focus on the eyes of the tiger. One might be tempted to think that Blake’s tiger was purely the creation of his poetic genius, an apt metaphor for the fiery deeps of hell. But historical evidence points to the fact that he may have seen an actual living tiger in the Tower of London. In those days, the Tower housed the royal menagerie – gifts for the Royal Family that were brought back by ship from far-flung countries. There was an elephant, as well as several leopards, lions and tigers, to name but a few species. Ferocious beasts were much sought after, especially since it was the prerogative of the Royal Family to own them. Within the Tower, they were kept in small cages. Sometime in the middle of the 18th century, this exhibition was opened to the public and so we might have found young William Blake having his own encounter with a tiger at far closer quarters than modern zoos allow for. The experience seems to have etched itself on his active mind and there is, in his poem, genuine awe at the splendour and beauty of the animal mingled with fear and a kind of nameless dread of its deadly power.

In a book entitled Animal Kingdom, in which he offers the spiritual significance of many animals, Sri Chinmoy equates the tiger with the quality of cruelty. He writes:

“Tiger, my tiger,

When are you going to end

Your dark cruelty-life?

How long shall wait at your door

Your divinity-friend?

Don’t delay! Don’t delay!

Inside the vital of your delay

Looms large your world-failure-day.” 3

In his poems, he invariably aligns the tiger with destructive qualities, such as ignorance, doubt and desire:

“The mind is a tiger,

An ignorance-tiger.

The heart is a fire,

A wisdom-fire,

To conquer the breath

Of the ignorance-tiger.” 4

“The ferocious ignorance-tiger

Is all around us.

This tiger may not be about to leave us

Right now,

But eventually it has to leave us

For good.” 5

“Self-doubt

Can be compared to

A ferocious, man-devouring

Tiger.” 6

Above all, he uses this powerful image to urge the spiritual seeker not to underestimate the power of the forces of ignorance, but to face those forces fearlessly and conquer them. He inspires us to cultivate within ourselves the same remarkable courage that he showed as a boy of ten and the same implicit faith in the ultimate victory of goodness, peace and divinity:

“Each time

You have a chance,

Hurl your wisdom-lance

At ignorance-tiger.” 7

“A man of belief

Compels the impossibility-tiger

To sit at his feet.” 8

– End –

Copyright © 2008, Vidagdha Bennett. All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.

Endnotes:

1 Excerpt from To the Streaming Tears of My Mother’s Heart and to the Brimming Smiles of My Mother’s Soul.

2 Excerpt from Reality-Dream.

3 Excerpt from Animal Kingdom.

4 Poem no. 17,815 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 179.

5 Poem no. 6,410 from Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 65.

6 Poem no. 5,311 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 54.

7 Poem no. 34 from My Fifty Gratitude-Summers.

8 Poem no. 16,767 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 168.

Those wishing to know more about the Royal Bengal Tiger may like to view: Climate Trackers: Bengal Tiger