This thesis was originally presented to& The Committee on the Study of Religion, Harvard College& in partial fullfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors — March, 1984

Table of Contents

Part I. Introduction and Background

Part I. Introduction and Background

Introduction

As Westerners, hence outsiders, we are most often struck by two aspects of Indian religion. At first, we are struck by the overwhelming multitude and diversity of forms in which God is worshipped. To our sensibilities, religion infects everyday life with almost brute force. In short, Indian religion is radically experiential in nature.

Next to this plethora of outer manifestations, perhaps even more striking is the astounding height and depth with which Indian philosophy probes the nature of the Cosmos, the amazing subtlety of the vision of reality it espouses.

In an attempt to bridge the cultural and philosophical gap between East and West, the study of Indian religion and philosophy, as it is practiced today, has adopted an essentially two-pronged approach.

First, there is the study of Indian religion as phenomena; that is to say, the study of the rituals and history of Indian culture in an attempt to understand the religious frame of mind within which Indians think. Second, there is the study of Indian religion as ideal; in other words, an examination of the mythic, epic, and philosophical texts with an eye towards gaining an understanding of the motivating forces behind those ritual and cultural phenomena.

While it is true that these two approaches to the study of Indian religion are often pursued independently of each other, it would be unfair to say that this is always the case. Often it is the intersection between myth and ritual that is of primary interest.

However, this particular interest in the juncture of myth and ritual, while certainly addressing itself to what we might call the popular outward tradition, fails to grasp its inward sustaining essence. Such a preoccupation with myth and ritual is not surprising. It is the natural outgrowth of the academic tradition out of which the Comparative Study of Religion has emerged, namely the phenomenologically oriented anthropological tradition of Levi-Strauss, Tyler, and more recently, Mircea Eliade.

Likewise, the study of Indian philosophy is more or less shaped by the presuppositions and methods of Western philosophy. That is, whereas Indian philosophy grows out of the realization of one’s own highest Self (which is none other than the highest Reality), the main attempt in Western philosophy is to establish an externally objectified and unchanging reality, against which we must verify our individual sense of reality. Indian philosophy, on the other hand, invites and encourages each individual to find their own ultimate reality within. Yet, it is understood that each individual’s ultimate reality fully partakes of a common, transcendent Reality.

In short, the mainstream approach to the study of Indian religion is largely the study of religious institutions. It is my contention, however, that a true understanding of Indian philosophy cannot be had by such means. To be sure, the myth and ritual of any religion reveal something of its deepest philosophical currents. Religion, however, almost by definition, concerns itself chiefly with that which is transcendent. Therefore, to gain the fullest understanding of Indian religion — indeed of any religion — we must look at the juncture not of myth and ritual, but of philosophy and practice.

Myth does not directly address the nature of reality; it only points to it by way of symbolism. Philosophy, on the other hand, has the description of reality, as best as words can serve the purpose, as its only goal. Ritual is often an appurtenance; it need not involve the sensibilities of an individual nor demand a fundamental change in one’s way of life. Practice, however, requires both a purposive understanding and an integration into one’s life.

Now, as has been mentioned, Hinduism is radically experiential in nature. That is, there is little value put on a mere intellectual understanding of the Cosmos; no, one must actually see for oneself through the veil of Maya and into the Unity beyond. One must make Truth one’s own. It is not enough to pray to God; one must see God, one goes to have darshan. This is the purpose of what I have called “practice” — to make the reality of Truth one’s own.

The concept of “scripture” in Indian religion bears out this emphasis on practice. Whereas the Western terms such as “scripture” and “Bible” imply some sort of written tract, the names of the two types of Hindu “scripture” reveal a much different sense. What we might call the primary texts of Hinduism, such as the Vedas and the Upanishads, are known as śruti, or “that which is revealed, or heard.” On the other hand, the popular corpus of literature, including the great epics of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, are known as sṃrti, literally “that which is remembered.” In both cases, then (though more so in the case of śruti), the sense of the term implies an active and personal process of transmission of a practicable philosophy.

The Upaniṣads belong to śruti or revealed literature, and are the utterances of sages who spoke out of the fullness of their illumined experience. They are the vehicles more of spiritual illumination than of systematic reflection. Their aim is practical rather than speculative. They give us knowledge as a means to spiritual freedom.1

To reiterate: the fullest meaning of Indian religion is to be found at the juncture of philosophy and practice. It is precisely those sages “who spoke out of the fullness of their illumined experience,” and whose aim is “practical rather than speculative,” who inhabit that juncture. However, the transmission of that illumined practical experience did not end with those sages of the hoary past. What characterizes Yoga is not only its practical side, but also its initiatory structure. One does not learn Yoga by oneself; the guidance of a master (Guru) is necessary.

Therefore, the process of transmission is an ongoing one, in which the Guru plays the pivotal role. The Guru can be likened to a spiritual communications satellite, receiving and decoding Truth from the Source on one end, and in turn passing that Truth on at the other. It is to the Guru, then, that we now turn our attention.

Historical Background

Far from being a neglected feature of Hinduism, in every age and school of thought, from the Upanishads to the present, Indian philosophy is replete with emphatic affirmations of the implicit necessity of a Guru. Furthermore, looking beyond overt references to the Guru, we find that a vast number of writings are couched as a Guru-disciple dialogue.2

Let us begin with the Upanishads. Whereas the Vedas proper are more important ritually, the Upanishads stand as the authoritative source of Indian philosophy. Belief in their authority can be considered, using Western terms, to be the basic article of faith of a Hindu. It is quite illumining, then, that the name Upanishad, derived from the three words upa- (near), ni- (down), and sad- (to sit), implies that they are the outgrowth of disciples “sitting down near” the feet of the Guru.3

The Muṇḍaka Upanishad provides us with perhaps the most concise example of the generalUpanishadicc notions of the importance of a Guru. The First Muṇḍaka, entitled, “Preparation for the Knowledge of Brahma,” begins with the following passage:

The line of tradition of this knowledge from Brahma himself

1. Brahma arose as the first of the gods –

The maker of all, the protector of the world.

He told the knowledge of Brahma, the

foundation of all knowledge,

To Atharva[n], his eldest son.2. What Brahma taught to Atharvan,

Even that knowledge of Brahma, Atharvan told

in ancient time to Angir.

He told it to Bharadvaja Satyavaha;

Bharadvaja, to Angiras – both the higher and the

lower [knowledge].4

Passages such as this are to be found at the beginning of Indian literature throughout history. Such passages are usually gestures meant to establish the writer’s authority by affirming the line of transmission from Brahma directly to the author. In so doing, such passages also serve to emphasize the way in which knowledge of Brahma is only passed on from one who already knows to one who aspires to know.

The last passage of the First Muṇḍaka explicitly reaffirms this idea:

This knowledge of Brahma to be sought properly from a qualified teacher

12. Having scrutinized the worlds that are built up

by work, a Brahman

Should arrive at indifference. The [world] that

was not made is not [won] by what is done.

For the sake of this knowledge let him go,

fuel in hand,

To a spiritual teacher who is learned in the

scriptures and established on Brahma.5

The implication here is clear. That which is not made cannot be won by our actions; we must depend on actions of the Guru to win it for us.

Moving on both chronologically and in order of importance, the Bhagavad-Gītā, in Chapter IV, entitled “The Way of Knowledge,” contains the following passage. Speaking about the superiority of knowledge over ritual action, Krishna tells Arjuna, “Learn that [knowledge] by humble reverence, by inquiry, and by service [to the Guru]. The men of wisdom who have seen the truth will instruct thee in knowledge.”6

In his commentary on this passage, the Indian philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan makes amply clear the meaning of Krishna’s injunction. He says,

Wise men will teach us the truth if we approach them in a spirit of service and reverent inquiry. Until we realize the God within, we must act according to the advice of those who have had the experience of God.7

Radhakrishnan’s first point is important; the Guru’s light can only be received if one is willing and receptive, otherwise, to use the electronic metaphor again, it is like trying to broadcast a television show to a television with no antenna.

Turning from śruti to sṃrti, in this case, the Srimad-Bhagavatam, we find the sage Narada in the midst of a discourse with King Yudhishthira on the means to enlightenment. After narrating a list of evils and how to overcome them (For example, “A man should conquer desire by foregoing resolutions, anger by renouncement of desire...”)8), Narada offers this piece of wisdom:

“O king! A person can speedily conquer all these through his unflinching devotion unto his preceptor... O king Yudishthira! A preceptor is rather identified with the Revered Lord Sri Krishna. He is lord of Prakriti and Purusha. The lotus-feet of a preceptor is sought after by people well versed in Yoga.”9

Marching on through history, we find the 10th century Tamil poet Alavandar singing these verses:

Adoration of God is more tasteful when done after the adoration of the blessed Guru, for, milk, though naturally sweet, is sweeter still when sugar is added to it.

Salutation again to Nathamuni, the worthiest among the self-controlled ones, who ... established in this world the all-comprehensive path of devotion through which is attainable the highest object of life.10

Of the handful of texts which scholars unequivocally attribute to the father of Advaita Vedanta, the great philosopher-sage Sankara, it is informative that one is a short work called the Upadeśasāhasrī. Meant as a manual for aspiring gurus on “how to teach the means to final release,” the very existence of the Upadeśasāhasrī serves as a testament to Sankara’s conviction about the necessity for a Guru. Sankara voices this conviction when he says, “When the text proceeds with the words ‘Thus have we heard’ it implies that the meaning of the texts ... has to be learned from the teachings of a Teacher...”11

A direct disciple of Sankara, and himself an important figure in the development of Advaita Vedanta, Suresvara echoes his Guru’s sentiment when he proclaims,

And without desire for liberation no one resorts to the feet of a teacher (Guru); and without association with a Guru there can be no hearing (śravaṇa) of the holy texts ... and without this nescience cannot be destroyed.12

Leaping into the 20th century, we find the conviction that a Guru is necessary has not diminished in the least. The Mahatma, the Great Soul, at one time the virtual father (bapu) of India, M.K. Gandhi, was by no means exempted from this yearning for a Guru. As he reveals in his autobiography,

I believe in the Hindu theory of Guru and his importance in spiritual realization. I think there is a great deal of truth in the doctrine that true knowledge is impossible without a Guru. An imperfect teacher may be tolerable in mundane matters, but not in spiritual matters. Only a perfect gñani deserves to be enthroned as Guru. There must, therefore, be ceaseless striving after perfection. For one gets the Guru that one deserves.13

Swami Vivekananda, the harbinger of the East, tells us,

There is no reason why each of you cannot be a vehicle of the mighty current of spirituality. But first you must find a teacher, a true teacher ... for us ordinary mortals a human teacher must come, and our preparation must go on till he comes.14

This last sentence, “our preparation must go on till he comes,” concisely expresses a parallel notion that is either explicitly or implicitly present throughout the passages quoted above, namely, that just as a Guru is necessary to attain realization, so a certain amount of preparation is necessary to gain a Guru. We will come back to this idea when we further discuss the role of a Guru in the chapters ahead.

Finally, I should note that the few examples presented here by no means represent an exhaustive search; one could certainly go on.15 However, I need only say that the necessity of a Guru is a primary assumption of Indian philosophy, and therefore permeates all that that philosophy has brought forth.

Part II. What is a Guru?

We have seen, from the historical evidence presented above, that the Guru plays an extraordinary role in the Indian spiritual consciousness. Such an extraordinary role requires an extraordinary person to play it. Indeed, we are bound to wonder what it is about these Gurus that merits their position as the ultimate mediators, as it were, between God and man. That is to say, what are the qualities (and qualifications) of a Guru?

For the most part, history describes the Guru in what to most would seem relatively subjective terms: a spiritual teacher is “established on Brahma”16; or the “meditative sage ... is a fathomless ocean of love divine and an unbroken expanse of incomprehensible, wonderful and unblemished knowledge and renunciation”17; or perhaps, the “Guru must be a man who has known, has actually realized the Divine Truth, has perceived himself as Spirit.”18

Nevertheless, there are some texts which provide us with a more objective summary of attributes. For example, the Upadeśasāhasrī of Sankara, his “Guru manual,” so to speak, houses within its pages an exhaustive checklist of prerequisite qualities for “Guruhood”:

And the Teacher is able to consider the pros and cons [of an argument], is endowed with understanding, memory, tranquility, self-control, compassion, favor and the like; he is versed in the traditional doctrine; not attached to any enjoyments, visible or invisible, he has abandoned all the rituals and their requisites; a knower of Brahman, he is established in Brahman; he leads a blameless life, free from faults such as deceit, pride, trickery, wickedness, fraud, jealousy, falsehood, egotism, self-interest and so forth; with the only purpose of helping others he wishes to make use of this knowledge.19

Fundamentally, I feel there are two responses to this passage: 1) on paper, it seems plausible, but one wonders how could such a person possibly exist; and 2) assuming such persons have existed or do exist, how might his or her personality be? How would he live his day-to-day life?

It is my firm conviction that such people have existed and do exist. Furthermore, as to the nature of their personality and daily life, I feel there is such a person alive today, a truly Self-realized man, whose life can provide us with ready answers not only to the questions at hand, but in addition to the greater questions raised above as to the deepest meanings of Indian philosophy. Such a man is Sri Chinmoy.

A Brief Biography

Sri Chinmoy (Chinmoy Kumar Ghosh) was born 27 August 1931 in Chittagong, in what was then East Bengal, India (and is now Bangladesh). The youngest of a family of seven children — father Shashi, mother Yogamaya, three sisters, and three brothers — Chinmoy (Chinmoy — “full of divine consciousness”) began life as a child much like any other. Always curious and full of mischief, the young Chinmoy soon gained the nickname “Madal,” or “little kettledrum.” Not lacking in cleverness, either, he was smart enough to ask his father for three of any toy; one to break, one to take apart to see how it worked, and finally, one to play with. Because mother and father encouraged their children in religious and spiritual matters, Chinmoy’s family proved a fertile environment for the young aspirant.

As the years passed, Chinmoy had several spiritual experiences which hinted at a vast spiritual height yet to be attained. Following the death of their father in 1942, and their mother the following year, the seven children moved to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry in South India. There, Chinmoy was able to devote himself intensely to his spiritual discipline and, shortly before his thirteenth birthday, he attained that spiritual height which various traditions call Self-realization, mokṣa, Nirvana, or to use Sri Chinmoy’s own term, God-realization.20

Now, the Western mind is tempted to find in a biographical sketch such as this, the psychological and historical factors which condition later actions and states of personality. However, in the case of a spiritual Master, such factors do not condition or explain his life as a Guru. Thus, we must be careful to distinguish between his human personality and his inner awareness of the Divine as it expresses itself through his day-to-day life. It is to this inner awareness, this realization, that we must look to find the motivating forces behind a Guru’s actions. Therefore, to understand the Guru’s actions, we must understand realization.

Realization is not only a goal, it is the journey to that goal as well. At the beginning of our journey, Sri Chinmoy writes,

We feel that we need God more than God needs us, but this is wrong. God needs us equally, if not more. Why? He knows our potentialities and possibilities infinitely better than we do. We feel that we can only go this far, but He knows that we can go millions of miles. We think of ourselves as useless, hopeless, helpless, but in God’s eyes we are really His divine instruments. He wants to use us in infinite ways. This is His Dream that He wants to transform into Reality. God wants us to be not only infinite but also eternal and immortal. He knows we have that capacity because he has given us the capacity.21

This is a challenge from God, or, in classical Hindu terms, this is God’s Game, His divine Lila. God is hiding, and He is asking us to seek Him. An earthly game of hide-and-seek lasts perhaps fifteen minutes, and our reward is to catch our earthly friends. But in God’s case, we are playing his eternal Game. Naturally, then, the Game will not last fifteen minutes, or fifteen days, or fifteen years, or perhaps even fifteen lifetimes. Indian philosophy tells us that as long as the Game has not ended, we must come back to Earth again and again until our seeking comes to an end and we have found God. Sri Chinmoy explains that when we finally do find Him,

... we consciously realise God, we come to know that we and God are absolutely one in both the inner life and the outer life. God-realisation means our identification with our absolute highest Self. When we can identify with our highest Self and remain in that consciousness forever, and when we can reveal and manifest it at our own command, that is God-realisation.22

For some, realization marks the end of their earthly journey; they have fought an age-long battle against ignorance, and they do not wish to reveal and manifest their realization. They are tired. They want to retire from the battlefield of life. Indeed, Sri Chinmoy would have been content to spend the rest of his life in the bliss of samādhi, if not for the following experience, which marked a turning point in his life;

Whenever I had the opportunity, I flew to the edge of the ever-blue sea and took my seat there in solitude. My bird of consciousness, dancing slowly, rose to the sky and lost itself up there.

On this occasion — it was a full-moon night — as I gazed and gazed upon the blue-white horizon, I found only light, a sea of sweet and serene light. All was engulfed, as it were, in an infinite Ocean of Light which played lovingly on the sweet ripples.

My finite consciousness was in quest of the Infinite and Immortal. I drank deeply of Ambrosia and was floating on an illumined ocean. It seemed that I no longer existed on this earth.

All of a sudden — I do not know why or how — something put an end to my sweet dream. No longer did the air emit its honey-like immortal Bliss, for my own depressed thoughts had come to the fore: “Useless, everything is useless. There is no hope of creating a divine world here on earth. It is only a childish dream.” I felt, too, that I could not go on even with my own life. This seemed to be nothing but a thorny desert strewn with endless difficulties.

“Why should I suffer these unbearable pains and sorrows here? I am the son of the Infinite. I must have freedom. I must have the ecstasy of Paradise. This ecstasy resides ever within me. Why then should I not leave this mortal world for my Eternal Abode in Heaven?”

A sudden flash of lightning appeared over my head. Looking up with awe and bewilderment, I found above me my Beloved, the King of the Universe looking at me. His radiant Face was overcast with sorrow.

“Father,” I asked, approaching him, “what makes Thy Face so sad?”

“How can I be happy, My son, if you do not wish to be My companion and help Me in my Mission? I have, concealed in the world, millions of sweet plans which I shall unravel. If My children do not help Me in My Play, how can I have My Divine Manifestation here on earth?”

Profoundly moved, I bowed and promised: “Father, I will be Thy faithful companion, loving and sincere, throughout Eternity. Shape me and make me worthy of my part in Thy Cosmic Play and Thy Divine Mission.” 23

In accordance with God’s invitation, as it were, Chinmoy spent the next two decades at the Ashram inwardly and outwardly preparing for his role in the Cosmic Play. Towards that end, Chinmoy determinedly strove for a balance between his inner life and his outer life. At the Ashram, he would attend daytime classes in Western education, where he studied, among other subjects, English, French, English composition (which he excelled at), English literature, music, and art. It was here that he developed a deep love for the writings of Keats and the other romantic poets, Emily Dickinson, Emerson, and, of course, Rabindranath Tagore. In addition to his studies, athletics played a major role in his Ashram life. Although he was an avid soccer player, his favorite sport was track and field, and especially sprinting. For sixteen consecutive years, Chinmoy was the Ashram champion in the 100-metre dash. Typical of his love for diversity, in addition, Chinmoy was twice decathlon champion.

His daytime outer activities done with, Sri Chinmoy would turn in the evenings to the cultivation of his inner life, often meditating into the early hours of the morning. During that time, he would practice entering and returning from the highest states of samādhi. As any airplane pilot will tell you, it is not the take-offs which are difficult, but rather the landings. So it is with samādhi. At first, upon returning from his meditative trance, Chinmoy would be quite disoriented; his friends would have to tell him his name, or he would wander about with one shoe on. He was, by his own admission, a first class “space cadet.”

But realization is said to be like a tree; one climbs to the top to reap the fruit, and then one can climb back down to share the fruit with others. Because Chinmoy wanted to share the fruit of his inner experiences, his inability to function normally upon “climbing down” was a stumbling block. Nevertheless, as with any discipline, regular practice renders natural and easy what was once difficult or impossible. So, through years of practice, Chinmoy was finally able to enter into and come down from samādhi with ease. He was then fully ready to offer the fruits of his realization to others. Following an inner call, in 1964 Sri Chinmoy left the Ashram, and on April 13th of the same year, reached the shores of America, where, amidst the hustle and bustle of New York City, he gradually assumed the role of a Guru.24

Expressing the Divine

On closer examination, the ways in which Sri Chinmoy plays his role as a Guru reveal three basic categories of action common to any Guru. The first, and by far the most important action the Guru performs is to inwardly teach meditation to his or her disciples. Sri Chinmoy affirms:

If you have a teacher who is a realised soul, his silent gaze will teach you how to meditate. A Master does not have to explain outwardly how to meditate or give you a specific form of meditation. He will simply meditate on you and inwardly teach you how to meditate ... All real spiritual Masters teach meditation in silence.25

Because of the private, inner nature of this teaching, it would be difficult if not impossible to provide much-supporting evidence for any assertions one might make about it. Also, there is neither one generalized teaching that every Master gives, nor one teaching that any given Master gives to each disciple. Each disciple is taught according to his or her capacity and needs. Therefore, due to the breadth and difficulty of the topic, it is unfortunately not within the scope of this essay to delve further into it.

By virtue of the fact that “a realised person can see, feel, and know what Divinity is in his own consciousness,”26 his outer actions, as expressions of his consciousness, will of their own accord be suffused with that Divinity. In this manner, the Guru’s second category of action functions as a channel for the Divine; that is to say, the Guru himself becomes an instrument of the Divine. For the most part, spiritual Masters have restricted their outer manifestation of Divinity to the written or spoken word, whether in prose or discursive form. In contrast, Sri Chinmoy’s hallmark is the great diversity of forms in which he expresses his inner awareness of Divinity. Specifically, the forms of expression we will now examine are: art, poetry, and music.

Art

Perhaps the most unique and compelling of Sri Chinmoy’s creative endeavors is his art, which he calls “Jharna-Kala” in Bengali, or “Fountain-Art.” It is unique because, if we are to judge by what has been left to posterity, very few spiritual Masters have been artists. Jharna-Kala is especially compelling because as an “embodiment of Truth-reality, which is manifested here in the form of art,”27 it is unequalled in its ability to express the sublimity of “Truth-reality,” to provide us with a palpable and lasting representation of that reality. This “Truth-reality” is none other than the Divine, of which the Guru acts as an instrument. In this vein, Sri Chinmoy says,

... if someone is a seeker-artist, then he is definitely under an obligation to embody the divine Consciousness in his art and to manifest the divine Consciousness in and through his art ... He himself is an instrument, and his paintings are also instruments ... If he is the instrument of something divine, then naturally he will be divine when he is creating, and his creation will follow its source.28

In this manner, Sri Chinmoy’s art can be seen as an extension of the Divine consciousness which is expressing Itself through him.

|

|

|

||

| A sampling of Sri Chinmoy’s 140,000 Jharna-Kala artworks. | ||||

Poetry

Within the context of certain Hindu religious communities (most notably the Tamil Saivites and Vaisnavas), the poetry of the bhakti poet-saints has long played an important a role in their religious and spiritual lives as Vedic and Upanishadic sources. So fervent is the belief in the illumining power of these bhakti poems, they have over the years been incorporated into the most sacred temple ceremonies. This belief stems precisely from the recognition of the poet-saints, and therefore, of their poetry, as instruments of the Divine.

Scholars commonly divide bhakti poetry into different categories, according to the mood the poems express. We can read Sri Chinmoy’s poetry with the same categories in mind. For example, consider the following:

IMMORTALITY

I feel in all my limbs His boundless Grace;

Within my heart the Truth of life shines white.

The secret heights of God my soul now climbs;

No dole, no sombre pang, no death in my sight.No mortal days and nights can shake my calm;

A Light above sustains my secret soul.

All doubts with grief are banished from my deeps,

My eyes of light perceive my cherished Goal.Though in the world, I am above its woe;

I dwell in an ocean of supreme release.

My mind, a core of the One’s unmeasured thoughts;

The star-vast welkin hugs my Spirit’s peace.My eternal days are found in speeding time;

I play upon His Flute of rhapsody.

Impossible deeds no more impossible seem;

In birth-chains now shines Immortality. 29

The poet has offered us a rare glimpse of the view from his lofty spiritual heights. It is as if the poet is reveling in the experience, but there is little to invite us to share in that experience. In the next poem, though, the poet is inviting us to participate in his experience and make it our own. The sense is that it is we who could just as easily have written the poem. Therein lies its power; the poem has the capacity to concisely express our deepest emotions, hopes and aspirations.

BORN TO DO SOMETHING GREAT

I was born to do something

Really great for God

On this planet.How can I fail?

Why should I fail? 30

Another mood we see often expressed is viraha, the pain of separation from God:

LORD OF BEAUTY

You are beautiful, more beautiful, most beautiful,

Beauty unparalleled in the garden of Eden.

Day and night may Thy Image abide

In the very depth of my heart.

Without You my eyes have no vision,

Everything is an illusion, everything is barren.

All around me, within and without,

The melody of tenebrous pangs I hear.

My world is filled with excruciating pangs.

O Lord, O my beautiful Lord,

O my Lord of beauty, in this lifetime

Even for a fleeting second,

May I be blessed with the boon

To see Thy Face. 31

This viraha mood finds its resolution when the lover and the Beloved are united in mutual love:

SWEET AND SECRET QUARRELS

Between my Lord Supreme and me

Have tremendously strengthened

Our secret love affair. 32

In addition to these classic bhakti moods, Sri Chinmoy employs a poetic device not commonly seen elsewhere: the mantric poem. These poems — usually short, infrequently rhyming, and frequently cryptic — are much like the utterances of the Yoga-Sutras. They are seldom meant to be understood literally; nor are they meant to be read only once. Only through a non-analytical repetition does their essence slowly unfold and become part of our consciousness:

You don’t have to understand.

Just believe.

You don’t have to believe.

Just keep your eyes wide open. 33My soul is the poet in me.

My heart is the poetry in me.

My Beloved Inner Pilot

Is the Reader in me. 34

Music

“It is through music that the Divine in us gets the opportunity to manifest itself here on earth.”35 With this utterance, Sri Chinmoy declares music’s special ability to reach straight to the heart of Truth. Indeed, “Music is the inner or universal language of God.”36 Music is unique in that it has the power to either transport us into the Divine, or to bring the Divine to us. “It is only music that has a free access to the Heart-Door of the Supreme. If you can feel that, then the musician in you will be able to manifest the highest.”37 It would be senseless for me to attempt an explanation of how it is that music achieves its effect.

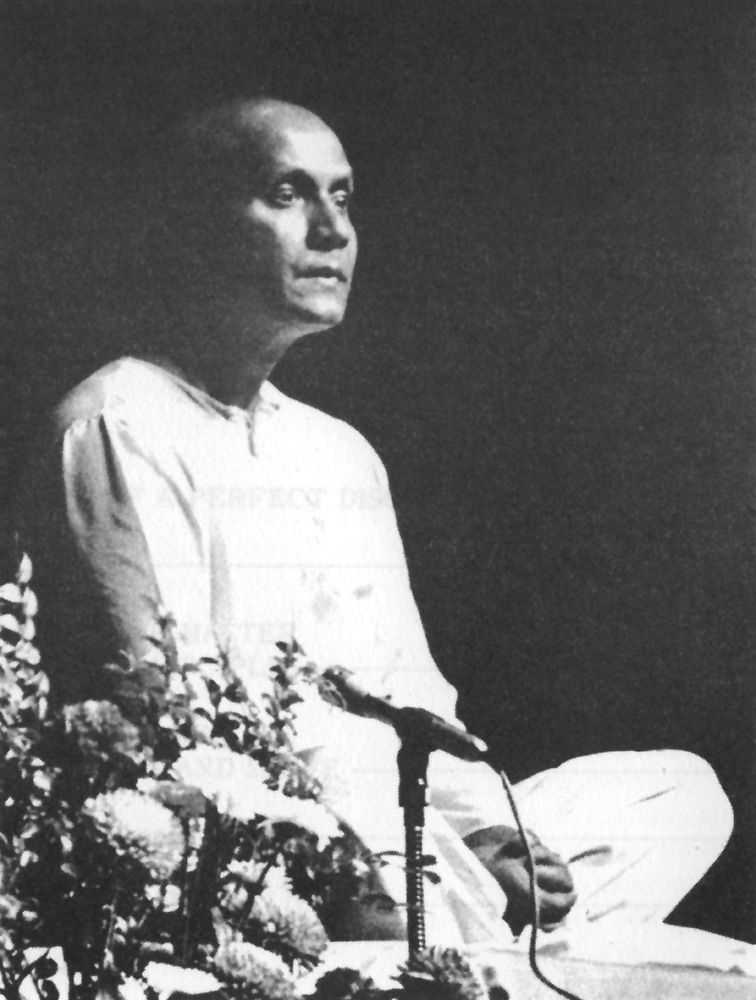

Sri Chinmoy sings one of his Bengali songs, Nayan Nehare

So, to express his inner awareness of Divinity, Sri Chinmoy, in his role as Guru, takes on the additional roles of poet, musician, and artist. Explaining his use of these roles, Sri Chinmoy says,

Each painting, each poem, each thing that I undertake is nothing but an expression of my inner cry for more light, more truth, more delight. If one painting or poem of mine inspires an individual to lead a better or higher life, then I shall feel that I have succeeded.38

In the third category of action, the Guru serves as an exemplar: by virtue of the fact that a Guru serves as a channel for the Divine (as we have just seen), he sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously (but always spontaneously) acts as a role model for those who seek the Truth he embodies. In Sri Chinmoy’s case, the two examples that stand out are running and self-transcendence.

Running and Self-Transcendence

For Sri Chinmoy, running is both a means and a metaphor. That is, the “outer running” and the “inner running” go hand in hand.

Running reminds us of our goal and at the same time makes us realise our need to reach our goal. Just as a marathon is a long journey outwardly, so is self-knowledge a long journey inwardly.39

As an avid runner himself, Sri Chinmoy seeks to inspire others to run in this very spirit. When approached as both a means and a metaphor, running helps the aspirant to

... try all the time to surpass and go beyond all that is bothering [him] and standing in [his] way ... so that ignorance, limitations and imperfections will all drop far behind [him] in the race.40

The ability to go beyond limitations, what Sri Chinmoy calls “self-transcendence,” is his primary characteristic as an exemplar. He says, “To transcend ourselves at every moment is our only goal.”41

Self-transcendence is our unerring march towards self-perfection or, in the terms which we have been using, the journey towards realization. The creative media we have discussed as means of expressing the Divine are Sri Chinmoy's primary avenues for self-transcendence, as well. This self-transcendence takes the form of an incredible fecundity.

For example, to date, Sri Chinmoy has written over 600 books of poetry, plays, stories, essays and commentaries. Of these written works there are, for example, one hundred talks given in twenty days,42 and 843 poems in twenty-four hours.43 In addition, Sri Chinmoy has painted over 140,000 paintings and drawings, 100,000 of which were painted between 19 November 1974 and 3 October 1975. Of those 100,000, Sri Chinmoy completed 16,031 paintings in a twenty-four-hour period. Also, he has composed over five thousand devotional songs.44

It may be hard to believe that such accomplishments could be humanly possible. In fact, Sri Chinmoy himself has said, “The human in me sincerely finds it difficult to believe, so how can you expect [Ripley’s] Believe It or Not to accept it?”45 It is only the Divine within each of us which is capable of such feats, a fact which Sri Chinmoy encourages others to realize for themselves. As a result, to cite one example, one of Sri Chinmoy’s students currently holds five records in the Guinness Book of World Records.46

In sum: by examining the categories of action the Guru engages in, we can begin to form an understanding of the nature of his realization as it expresses itself through his day-to-day life.

Part III. Conclusions

We have seen the primary importance (as is borne out by history) of a Guru within the context of Indian philosophy. By an examination of the life of Sri Chinmoy as paradigmatic of Gurus in general, we have attempted to answer the question of how — by the role he plays — the Guru merits his position in the cosmic scheme. In this respect, Sri Chinmoy should be seen as an example, as symbolic of the potential within everyone, not as the unique possessor of that potential.

It should be clear that, if we are to characterize the Guru in terms of his cosmic role, it is his position at the juncture between philosophy and practice, between the human and the Divine, that places him at the center of the Indian spiritual quest.

Given the central role of the Guru, what light can this shed on our understanding of Indian philosophy as a whole? I have said that religion is chiefly concerned with the transcendent. For Indian (and, indeed, any) philosophy to be tenable as a vision of ultimate reality, and act as a force for change in people’s lives, there must be a way of bridging the gap between our mundane existence and the transcendent reality to which we aspire. We need to grasp that which is by its very nature — “neti neti”47 — is ungraspable. We need to assign some form to that which is formless.

The Guru is that bridge. He has that which we seek to grasp. He embodies the formless with form. As such, the Guru is the most powerful symbol we have for all that Indian philosophy has to offer. The Guru reveals the infinite potential of the inner world of the formless Divine, while living his life amidst the outer world of form. Through his multifarious activities, which spontaneously spring from his union with the Divine, the Guru illustrates the One manifesting Itself as the many. Finally, the Guru provides us with a means of approaching that which is otherwise beyond the flight of our imagination. As his self-realization gradually unfolds itself in his outer manifestation, we can almost hear the immortal words of the sages echoing through the ages, “Tat tvam asi...,”48 “That thou art...”

— End —

Endnotes:

1 Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and Charles A. Moore, A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), p. 37.

2 See also Chandogya Upanishad, 8.1., Prasna Upanishad 3-6, Maitri Upanishad 2-4.

3 idem, A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy.

4 Robert Ernest Hume, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, 2nd ed. (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), p. 366.

5 ibid., p. 369.

6 Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., The Bhagavadgita (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1973), p. 169.

7 ibid.

8 J. PI. Sanyal, trans., The Srimad-Bhagavatam (New Delhi: Mushiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1973), p. 690.

9 ibid.

10 Swami Ramakrishnananda, Life of Sri Ramanuja (Mylapore: Sri Ramakrishna Math), p. 2.

11 A.J. Alston, Samkara on the Absolute: A Samkara Source-Book vol 1. (London: Shanti Sadan, 1980), p. 162.

12 Sri Suresvara, The “Naiskarmya Siddhi” [The Realization of the Absolute], 2nd ed. trans. A.J. Alston (London: Shanti Sadan, 1971), p. 78.

13 M.K. Gandhi, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957), p. 89.

14 Swami Vivekananda, Raja-Yoga 2nd ed. (New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1982), p. 277.

15 See also e.g. The Laws of Manu 2.146, 2.153, 2.225-235.

16 Samkara, Upadesasahasri cited in A Sourcebook of Advaita Vedanta (Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1971), p. 124, from unpublished trans. by Sengaku Mayedu.

17 Ramakrishnananda, p. 102.

18 Vivekananda, p. 279.

19 Samkara, p. 125.

20 The relationship between the Master and the disciple is by and large an inner one (see p. 22 above), and as Sri Chinmoy has not elaborated on that relationship, I do not speculate on the nature of Sri Aurobindo’s role in Sri Chinmoy’s life.

21 Sri Chinmoy, Light of the Beyond: Teachings of an Illumined Master (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1979), p. 181.

22 ibid., p. 182.

23 Sri Chinmoy, Awakening, 1988, Citadel Books, Scotland, p.49.

24 Biographical information from Zwarenstein, p. 3, and disciple sources.

25 Sri Chinmoy, A Sri Chinmoy Primer (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1974), p. 97.

26 Sri Chinmoy, The Summits Of God-Life: Samadhi And Siddhi (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1974).

27 Zwarenstein, A Fountain of Art: A Study of the Painting of Sri Chinmoy. Zurich: Verlag Bewusstes Dasein. 1981, p. 49.

28 ibid., p. 53.

29 Sri Chinmoy, My Flute (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1975), p. 10.

30 Sri Chinmoy, Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 33 (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1982), no. 3224.

31 idem. My Flute, p. 58.

32 idem. Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 23, no. 2287.

33 Cited in a lecture given by Alan Spence, Columbia University, 14 August 1982.

34 Sri Chinmoy, Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 16 (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1983), no. 1541.

35 Sri Chinmoy, God the Supreme Musician, rev. 2nd ed. (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1576). p. 11.

36 ibid., p. 41.

37 ibid., p. 52.

38 Sri Chinmoy, Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, afterword to the series.

39 The Sri Chinmoy Runner’s Logbook (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1981), p. 24.

40 ibid., p. 66.

41 Unpublished lecture by Sri Chinmoy, 1 November 1980.

42 See Sri Chinmoy, Everest-Aspiration (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1978).

43 See Sri Chinmoy, Transcendence-Perfection (Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1974).

44 Based on official disciple records.

45 Unpublished talk by Sri Chinmoy, 3 October 1975.

46 See Guinness Book of World Records, paperback ed., Bantam, 1984.

47 Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, 4.5.15.

48 Chandogya Upanishad, 6.9.1-4.

Selected Bibliography

Alston, A.J. Samkara on the Absolute: A Samkara Source-Book, Vol. 1. London: Shanti Sadan, 1981.

Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, A.C. The Spiritual Master and the Disciple. Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1978.

Deutsch, Elliot, and van Buitenen, J.A.B. A Source Book of Advaita Vedanta. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1971.

Eliade. Mircea. Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Bollinger Series, LVI. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1970.

Gandhi, M.K. An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth. Boston: Beacon Press, 1957.

Hume, Robert Ernest. The Thirteen Principal Upanishads. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1931.

Lingat, Robert. The Classical Law of India. Translated by J. Duncan M. Derrett. London: University of California Press, Ltd., 1973.

Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli, and Moore, Charles A., eds. A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

Radhakrishnan, S., trans., The Bhagavadgita. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1973.

Ramakrishnananda, Swami. Life of Sri Ramanuja. Mylapore:

Sri Ramakrishna Math, no copyright.

Ramanujachari, C. The Spiritual Heritage of Tyagaraja. 2nd ed. Mylapore: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1966.

Sri Chinmoy. God the Supreme Musician. rev. 2nd ed. Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1976.

Light of the Beyond: Teachings of an Illumined Master. Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1979.

The Sri Chinmoy Runner's Logbook. Jamaica, N.Y.; Agni Press, 1981.

Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 23. Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1982.

Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 33. Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1982.

Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 16. Jamaica, N.Y.: Agni Press, 1983.

Sri Suresvara. The “Naiskarmya Siddhi” [The Realization of the Absolute]. Translated by A.J. Alston. 2nd ed. London: Shanti Sedan, 1971.

Vivekananda, Swami. Raja-Yoga. 2nd ed. New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1956.

Vyasa, Krishna-Dwaipayana. The Srimad-Bhagavatam, Vol. 1. Translated by J.M. Sanyal. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1973.

Zwarenstein, A.S. A Fountain of Art: A Study of the Painting of Sri Chinmoy. Zurich: Verlag Bewusstes Dasein. 1981.

Copyright © 2010, Aparajita (Adam) Fishman.

All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.