Sri Chinmoy graced this earth for seventy-six years, but his life nearly ended after barely three years when he contracted such a severe case of smallpox that the doctors gave up hope for his survival. Had their prognosis been correct, the world would have lost one of its most revered spiritual leaders at the very dawn of his life. The story of how the infant Madal survived against all odds is a testament to the miraculous power of prayer – in this case, the ceaseless prayers and unwavering faith of his mother, Yogamaya.

From time immemorial, smallpox has been one of mankind’s greatest killers. Lord Macaulay, in his History of England (1914), described it as “the most terrible of all ministers of death.” During the 20th century alone, it is estimated that smallpox was responsible for 300-500 million deaths.

In 1958, at the height of the Cold War, the Soviets requested a global campaign to eliminate smallpox. Their proposal met with universal support and, by the end of 1979, the World Health Organisation was finally able to certify the eradication of smallpox ‘in the wild’. In May the following year, the World Health Assembly declared: “The World and all its peoples have won freedom from smallpox, which was a devastating disease sweeping in epidemic form through many countries since earliest times, leaving death, blindness and disfigurement in its wake, and which only a decade ago was rampant in Africa, Asia, and South America.” To date, smallpox remains the only human infectious disease to have been completely eradicated.

In 1934 or ’35, when Madal succumbed to the disease, India was the stronghold of smallpox in Asia. Bengal, in particular, was subject to such frequent epidemics that the disease was known as Bashanta, meaning ‘spring’, because that was the season during which these disastrous epidemics regularly occurred.

As early as 1880, the British rulers of India had passed a Vaccination Act requiring children to be vaccinated against smallpox within six months of birth, but it seems that the Act did not apply to all jurisdictions and it was not enforced, especially in rural areas. Vaccination teams went from village to village, but they were inadequate to the enormous task and their work was impaired by administrative apathy, as well as suspicion and mistrust on the part of the Indians. As a result, it seems that the small village of East Shakpura where the Ghosh family lived was somehow overlooked between the years spanning Madal’s birth in 1931 and his contraction of the disease.

In spite of his protected village upbringing, somehow the young Madal must have been exposed to someone who carried the disease. Since no other member of the family suffered from smallpox, it seems most likely that the carrier was someone outside the family circle, possibly a housemaid, cook or gardener who stopped to play with the little child. The near-tragedy that ensued is related in Sri Chinmoy’s own words:

“When I was three or four years old, I had the worst possible case of smallpox. The smallpox attacked my eyes, ears and nose – everything. The doctor said it was a matter of weeks: I would die or I would go blind or become deaf. The case was so serious. My mother said, ‘With God’s Blessings and my prayers, I will not allow my youngest son to die or to become blind or deaf.’

The doctors said, ‘We do not want your son to die, but he is going to die. Our medicine will not work.’

My mother accepted the challenge. She used to wash my face with coconut water. Her prayer and coconut water saved me. I am not dead; I am not blind or deaf. I may have the marks on my face, but my case would have been infinitely worse if the smallpox had not left me. I was cured only because of my mother’s prayer to God and her concern and affection for me. She saved my life.” 1

I imagine that most contemporary readers, like myself, have only a vague idea of the effects and ravages of smallpox. We know, for example, that such notables as Mozart, Beethoven, Elizabeth I of England, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln were afflicted with the disease and survived it, though all of them bore visible pockmark scars as a result. In 1801 President Thomas Jefferson had introduced mandatory smallpox vaccinations for American Indians. This followed the breakthrough discovery by Edward Jenner in 1796 that those who were inoculated with cowpox virus developed immunity to smallpox. In spite of the development of vaccines, however, this devastating scourge lingered in both Western and Eastern countries.

There are two virus variants of smallpox: Variola major and Variola minor. Variola major, the more deadly of the two, was more prevalent in Asia, while Variola minor occurred predominantly in Europe. It is evident from Sri Chinmoy’s description that he contracted Variola major. The overall mortality rate of this variant was around 30-35%.

Smallpox is transmitted from one human being to another by inhaling virus-laden droplets released into the air by coughing or sneezing. Children are particularly susceptible to the contagion. The incubation period is about 12 days. After that time, the victim develops an acute fever that can soar over 104ºF (40ºC). This is frequently accompanied by severe headaches, muscle pains, chills and vomiting. By days 12-15, the first visible lesions appear on the mouth, tongue, palate and throat. These lesions rapidly enlarge and rupture. Within another 24-48 hours, a burning rash appears on the skin, typically on the forehead, and then spreads to the whole face, extremities and torso. By the second day of the rash, the skin lesions erupt in sharply raised and hard pustules. The distribution of the pustules is densest on the face.

Treatment is supportive only and consists primarily of wound care and infection control. The well-defined aspects of Variola major are high fever, deep rashes and oozing pustules.

In Madal’s case, as his symptoms worsened, it seems that the doctors who had been called in to treat him gave up all hope of his survival. Even the family priest abandoned hope. Sri Chinmoy writes:

“At one point during my illness, my smallpox was getting worse day by day. Not only the doctor but also the family priest felt that I would not survive. One night the priest dreamt that I had died. He ran to our house immediately, in the dead of night, and knocked at our door. My mother, quite alarmed, opened the door. The priest rushed toward me while I was fast asleep inside the mosquito net. My suffering had been most pitiful until then, but I awoke suddenly, screaming a healthy cry. Upon hearing me, the priest started striking his chest with his fists, in joy or dismay or both, and tearing his hair out at the roots. ‘O God,’ he cried, ‘You have deceived me. But my heart is overwhelmed with joy and gratitude at Your deception.’

My mother wanted to know why the priest had come at this late hour, so the priest, still trembling, told her all about the dream he had had. My mother replied, ‘Venerable sir, my prayer is infinitely stronger than a child’s smallpox.’ ” 2

And so, against all odds, Madal lived. The effect of the coconut water perhaps minimised the infection and cooled his skin, but clearly it did not cure him.

|

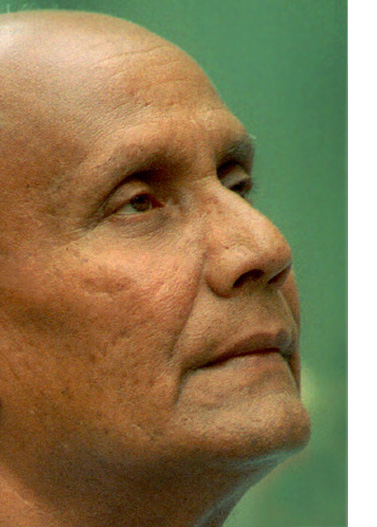

| A close-up of Sri Chinmoy showing smallpox scars still in evidence after sixty years. Photo courtesy: Pavitrata Taylor |

One can only marvel at the power of his mother’s prayers which drew him back from the grasp of death. She pitted her faith against this great scourge and won. Nor did her son suffer from after-effects such as blindness, deafness or disfigurement following his long recovery. Only in a certain light, if one looked closely at Sri Chinmoy’s golden countenance, could one faintly discern the dark purplish scars that indicated where the eruptions had been.

In an interview conducted on December 15th, 2008, a longtime student of Sri Chinmoy offered some valuable insights into Sri Chinmoy’s smallpox condition:

“When the British were in Burma, which was at that time a British possession, they came into East Bengal, which we now call Bangladesh. They came there to reinforce their control of Burma. Sri Chinmoy’s mother told him that when he was an infant, he was so beautiful that the British soldiers were always carrying him around. I once said to him, ‘Did your family know they were British soldiers?’ He answered, ‘Yes, but since they were the conquerors my parents could not say: Do not pick up my child.’ The soldiers liked him very much, but when he was three years old, he contracted smallpox which left ugly lesions on his face. With smallpox there are scabs and, when the scabs heal, they drop off or the child scratches them and then it leaves a scar. So Sri Chinmoy said that he never was as beautiful after the smallpox as he was before. Smallpox was such a rampant disease in those days that many, many people got it. Even though Sri Chinmoy’s father was quite wealthy, it did not prevent his own child from getting a disease that was very widespread.”

In the poetry of his later years, Sri Chinmoy did not specifically invoke the sights and sounds of his beloved Bengal, nor did he convey highly personal experiences. He subsumed them into his vision of mankind’s spiritual progress. But his childhood impressions did not vanish altogether from his memory. Thus we find him yoking the negative aspects of the human mind with words such as ‘disease’, ‘fever’, ‘contagious’, ‘infectious’, ‘chronic’ and ‘incurable’ – words that we might employ in everyday use, but which attain a profound significance in view of the fact that he very nearly lost his life to smallpox.

“You are not the only one

Who suffers from

The infectious doubt-disease.

Doubt-disease has covered

The length and breadth

Of the world.” 3

“Ungratefulness

Is the incurable disease

Of millennia.” 4

“Despair-fever

Is, indeed,

A fatal disease.” 5

“Temptation is the world’s

Oldest disease.

Aspiration is at once

The world’s most ancient

And most modern medicine.” 6

There are even references to the potential blindness and disfigurement that might have resulted from his bout with smallpox:

“The mind’s doubt-disease

Disfigures

The entire being.” 7

“Desire-fever tortures

The human mind.

With brutal force it renders

The heart-eye blind.” 8

Finally, there is this prescient poem in which the poet appears to refer to the span of his life in the third person:

“From Heaven

He came into the world

With an unconscious headache.

From earth

He will return to Heaven

With a conscious fever.” 9

In view of the fact that during his final days on earth Sri Chinmoy was subject to an unremitting fever, this last line seems to contain both an actual and a metaphorical truth. Inwardly, he willingly took upon himself the imperfections of humanity in order to illumine and transform them. Outwardly, this supreme act of love caused him to suffer from a fever that no amount of medical assistance could reduce. One thing we know for certain: the scorching fevers that marked both the dawn of Sri Chinmoy’s life and its close were both subject to the Will of God.

– End –

Copyright © 2009, Vidagdha Bennett. All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.

Endnotes:

1 Excerpt from To the Streaming Tears of My Mother’s Heart and to the Brimming Smiles of My Mother’s Soul.

2 Excerpt from To the Streaming Tears of My Mother’s Heart and to the Brimming Smiles of My Mother’s Soul.

3 Poem no. 3,030 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 31.

4 Poem no. 13,183 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 132.

5 Poem no. 10,829 from Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, Part 11.

6 Poem no. 2,769 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 28.

7 Poem no. 10,819 from Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, Part 11.

8 Poem no. 46 from Silence Speaks, Part 9.

9 Poem no. 1 from The Silence-Song.